WAMBS Checklist in JASP (using JAGS)

Ihnwhi Heo and Rens van de Schoot

Department of Methodology and Statistics, Utrecht University

Last modified: 02 October 2020

This tutorial illustrates how to follow the When-to-Worry-and-How-to-Avoid-the-Misuse-of-Bayesian-Statistics (WAMBS) Checklist (Depaoli and Van de Schoot, 2017) in JASP (JASP Team, 2020) using JAGS. Among many analytic techniques, we focus on the regression analysis and explain the 10 points for the thorough application of Bayesian analysis. After the tutorial, we expect readers can refer to the WAMBS Checklist to sensibly apply the Bayesian statistics to answer substantive research questions.

There are four preparatory tutorials in JASP that we provide. For readers who want to learn the fundamentals of JASP, we recommend reading JASP for beginners. For those who need nuts and bolts of Bayesian analyses in JASP, we suggest reading JASP for Bayesian analyses with default priors. For those who are keen on incorporating informative priors in JASP using JAGS, we guide you to read JASP for Bayesian analyses with informative priors (using JAGS). For those who need an advanced understanding of Bayesian regression in JASP, we recommend following Advanced Bayesian regression in JASP.

Since we continuously improve the tutorials, let us know if you discover mistakes, or if you have additional resources we can refer to. If you want to be the first to be informed about updates, follow Rens on Twitter.

How to cite this tutorial in APA style

Heo, I., & Van de Schoot, R. (2020, October). Tutorial: WAMBS Checklist in JASP (using JAGS). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4001366

PhD-Delays Dataset

We will use a phd-delay dataset (Van de Schoot, 2020) from Van de Schoot, Yerkes, Mouw, and Sonneveld (2013). To download the dataset, click here.

The dataset is based on a study that asks Ph.D. recipients how long it took them to complete their Ph.D. projects (n = 333). It turned out that the Ph.D. recipients took an average of 59.8 months to finish their Ph.D. trajectory.

For more information on the sample, instruments, methodology, and research context, we refer interested readers to the paper (see references). A brief description of the variables in the dataset follows. The variable names in the table below will be used in the tutorial, henceforth.

| Variable name | Description |

|---|---|

| B3_difference_extra | The difference between planned and actual project time in months |

| E4_having_child | Whether there are any children under the age of 18 living in the household (0 = no, 1 = yes) |

| E21_sex | Respondents’ gender (0 = female, 1 = male) |

| E22_Age | Respondents’ age |

| E22_Age_Squared | Respondents’ age-squared |

How to cite the dataset in APA style

Van de Schoot, R. (2020). PhD-delay Dataset for Online Stats Training [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3999424

Preparation

1. Setting a goal: A research question

- Earning a Ph.D. degree is a long and enduring process. Many factors are involved in timely completion, abrupt termination, or some delay of the Ph.D. life. For the current tutorial, we examine how age is related to the Ph.D. delay.

- Let’s think about the relationship between age and Ph.D. delay. Do you think they are linearly related? Are there any different ideas such that the age is non-linearly associated with the delay? We expect the relationship between the completion time and age are non-linear. This might be because, at a certain point in your life (say mid-thirties), family life takes up more of your time compared to when you are in the twenties.

- To that end, we examine whether the age of the Ph.D. recipients predicts a delay in their Ph.D. projects. The regression model is consequently the one we should adopt to answer the research question. We use the difference variable (B3_difference_extra) as the dependent variable and the age (E22_Age) and the age-squared (E22_Age_Squared) as the independent variables for the regression model.

2. Understanding the data

Loading data

- The statistical analysis goes hand in hand with data. If you have not yet downloaded the dataset for our tutorial, click here.

- JASP offers three ways to load the data with simple mouse clicks: from your computer, the in-built data library, or the Open Science Framework.

- If you are not familiar with loading the data, please go to JASP for beginners and see how to load the data.

- It’s time to meet the data in JASP. Did you successfully load your dataset? The column names should correspond to the names of the five variables in the dataset.

Exploring data with descriptive statistics

- Let’s see the descriptive statistics of the variables to check whether all the data points make sense.

- Click Descriptives at the top bar to proceed with -> Move all the variables to space under the Variables section -> Check Frequency tables (nominal and ordinal variables) -> Click Statistics -> Check additional descriptive statistics (S. E. mean under Dispersion, Median under Central Tendency, and Skewness and Kurtosis under Distribution) for better understanding

- If you are not familiar with data exploration, please go to JASP for beginners and check how to inspect the data.

- For all the variables, the sample size is 333 without any missing values.

- For the difference variable (B3_difference_extra), the mean and the standard error of the mean are 9.97 and 0.79.

- For the age variable (E22_Age), the mean and the standard error of the mean are 31.68 and 0.38.

- For the age-squared variable (E22_Age_Squared), the mean and the standard error of the mean are 1050.22 and 35.97.

- For the dichotomous variables (E4_having_child and E21_sex), frequency tables are presented.

- Given the descriptive statistics, all the data points substantively make sense.

Inspecting data visually

- Let’s plot the expected relationship between age and the delay for visual inspection. To do that, we need to remain only two variables, B3_difference_extra and E22_Age, under the Variables section.

- Click Plots and check Scatter Plots -> Under Scatter Plots, uncheck Show confidence interval 95.0%. We can see the scatter plot between the difference variable on the x-axis and the age variable on the y-axis.

- Although we can use this scatter plot for our visual inspection purposes, it might be better to locate the difference variable on the y-axis and the age variable on the x-axis since we regress the difference variable on the age variable. We can simply do that by changing the variable order under the Variables section: set E22_Age to be the first and B3_difference_extra the latter.

- With this plot, we can see the non-linear relationship between the difference variable and the age variable.

- It is also possible to examine the linear relationship by drawing the linear regression line. How? Uncheck Smooth and check Linear under Add regression line. Can you see the linear line?

Stage 1. Do you understand the priors?

Point 1. Do you understand the priors?

- We first need to think about the prior distributions and their hyperparameters for our regression model. Hyperparameters are the parameters for the prior distributions.

- The regression model for the current example can be written as: \(Difference = b_{0} + beta_{Age} * X_{Age} + beta_{Age-squared} * X_{Age-squared}\)

- In our regression model, parameters are the intercept, two regression coefficients, and residual variance. Thus, we should specify the prior distributions for the intercept, two regression coefficients, and residual variance, respectively.

Prior distribution for the intercept

- For the intercept, we use the normal prior \(\mathcal{N}(\mu_0, \ 1/\sigma^{2}_{0})\), where \(\mu_0\) is the mean and \(\ 1/\sigma^{2}_{0}\) is the precision of the distribution.

- JAGS uses not variance but precision. The precision is the inverse of the variance. For example, the precision of 0.01 is equal to the variance of 100 (the inverse of 0.01 is 100).

- In specifying the precision, we use the form of ‘1/variance’ since variance is more intuitive than precision for us.

Prior distributions for the regression coefficients

- For the regression coefficient of the age variable, we use the normal prior \(\mathcal{N}(\mu_1, \ 1/\sigma^{2}_{1})\), where \(\mu_1\) is the mean and \(\ 1/\sigma^{2}_{1}\) is the precision of the distribution.

- For the regression coefficient of the age-squared variable, we use the normal prior \(\mathcal{N}(\mu_2, \ 1/\sigma^{2}_{2})\), where \(\mu_2\) is the mean and \(\ 1/\sigma^{2}_{2}\) is the precision of the distribution.

Prior distribution for the precision

- In a normal regression model, the inverse gamma distribution is used as a prior for the variance thanks to the conjugacy (Lynch, 2007). Keep in mind, however, that JAGS uses the precision instead of the variance. Therefore, we have to consider prior distributions for the precision.

- To do that, we should use the gamma distribution as a prior for the precision. In other words, using a gamma distribution on the precision is the same as using an inverse gamma distribution on the variance (think about the inverse relationship!).

- For the precision, we use the gamma distribution \(Gamma(\kappa_0,\theta_0)\), where \(\kappa_0\) is the shape parameter and \(\theta_0\) the rate parameter of the distribution, as the prior distribution.

Choosing values for the hyperparameters

- Next, we specify the actual values for the hyperparameters of the prior distributions. Researchers can choose the hyperparameters based on the previous study, experts’ knowledge, plausible parameter space, for instance. Let’s say we found the previous study and base the current study with the following hyperparameters:

- \(intercept \sim \mathcal{N}(-35, 1/20)\)

- \(\beta_1 \sim \mathcal{N}(0.8, 1/5)\) where beta1 refers to the regression coefficient of the age variable.

- \(\beta_2 \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1/10)\) where beta2 refers to the regression coefficient of the age-squared variable.

- \(tau \sim Gamma(.5, .5)\) where tau refers to the precision. This setting is an uninformative prior for the precision, which has been found to perform well.

Stage 2. Run the model and check for convergence

- To run the model, we have to type the JAGS code that species the model in JASP.

- If you click the JAGS button on the top bar, you encounter the control panel to feed the code into the Enter JAGS model below section.

- What we have to do next is to write the JAGS model code.

- If you want to refer to the brief JAGS grammar to specify the model, please read the corresponding part in JASP for Bayesian analyses with informative priors (using JAGS).

- Readers can find the extensive JAGS manual at the mcmc-jags project. We also refer readers to RJAGS: how to get started that illustrates how to run the JAGS but in R.

- The JAGS model for the current example can be specified as:

model{

# likelihood

for (i in 1:333){

mu[i] <- intercept + beta1 * E22_Age[i] + beta2 * E22_Age_Squared[i]

B3_difference_extra[i] ~ dnorm(mu[i],tau)

}

# priors

intercept ~ dnorm(-35,1/20)

beta1 ~ dnorm(0.8,1/5)

beta2 ~ dnorm(0,1/10)

tau ~ dgamma(0.5,0.5)

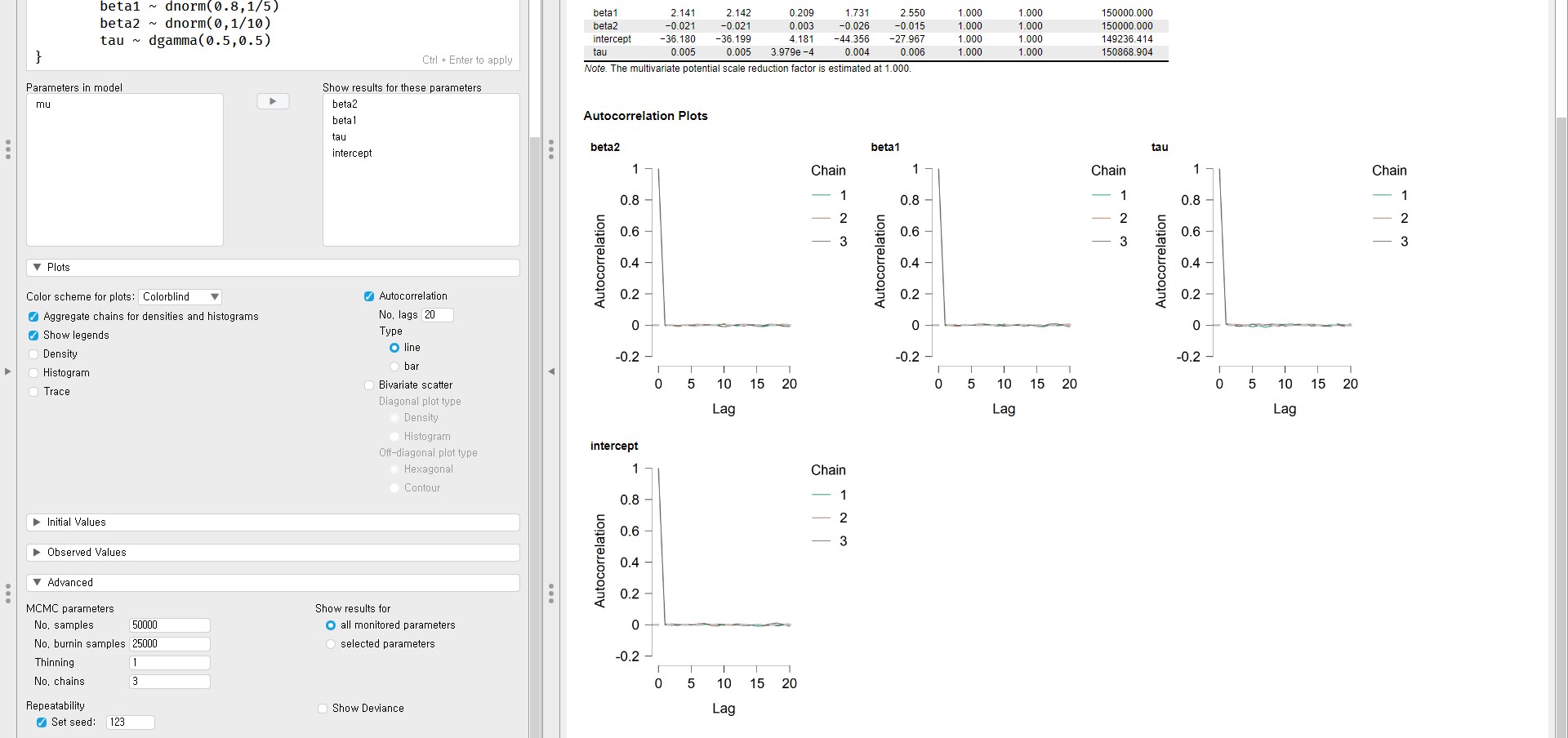

}- Before running this code, we set a seed of 123 for reproducible results. To do that, click the Advanced option in the control panel. Below Repeatability, type 123 for the seed.

- If you are unfamiliar with the reason why we set a seed value in conducting Bayesian statistics, please read Advanced Bayesian regression in JASP.

- Copy and paste the code into the Enter JAGS model below section.

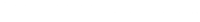

Point 2. Does the trace plot exhibit convergence?

- First, we only use 10 burn-in samples and take 50 samples. In other words, the number of iterations is 60.

- Click Advanced in the control panel -> Type 50 in No. samples (i.e., the number of samples) and 10 in No. burnin samples (i.e., the number of burn-in samples)

- Go again to the code that we have pasted. Press Ctrl and Enter on the keyboard together to apply the code. With this action, you are running the model that we specified.

- To see the trace plots for the parameters, move intercept, beta1, beta2, and tau from the Parameters in the model section to the Show results for these parameters section.

- In the control panel, check Trace in the Plots tab.

- With the trace plots, we can examine whether the parameter estimates from multiple chains are stable. If the trace plots are indistinguishable, this indicates that we do not need to increase the number of iterations.

- According to the trace plots of the four parameters, we see that the chains have not converged into one another yet. The ideal trace plot should exhibit one fat caterpillar. Thus, we need to increase the number of iterations.

- In addition to the trace plots, the convergence diagnostics tell us whether the chains have converged. One such convergence diagnostic is the Gelman and Rubin diagnostic. In the output panel, JASP provides the Gelman and Rubin diagnostic. Where? The Rhat column of the MCMC Summary table!

- If the multiple chains have converged neatly, the point estimate (Point est.) and the upper limit of the confidence interval (Upper CI; also referred to as the upper confidence limit) should be close to 1. According to the MCMC Summary table, the point estimate and the upper confidence limit of beta1, for example, is not close to 1. Therefore, we decide to increase the number of iterations.

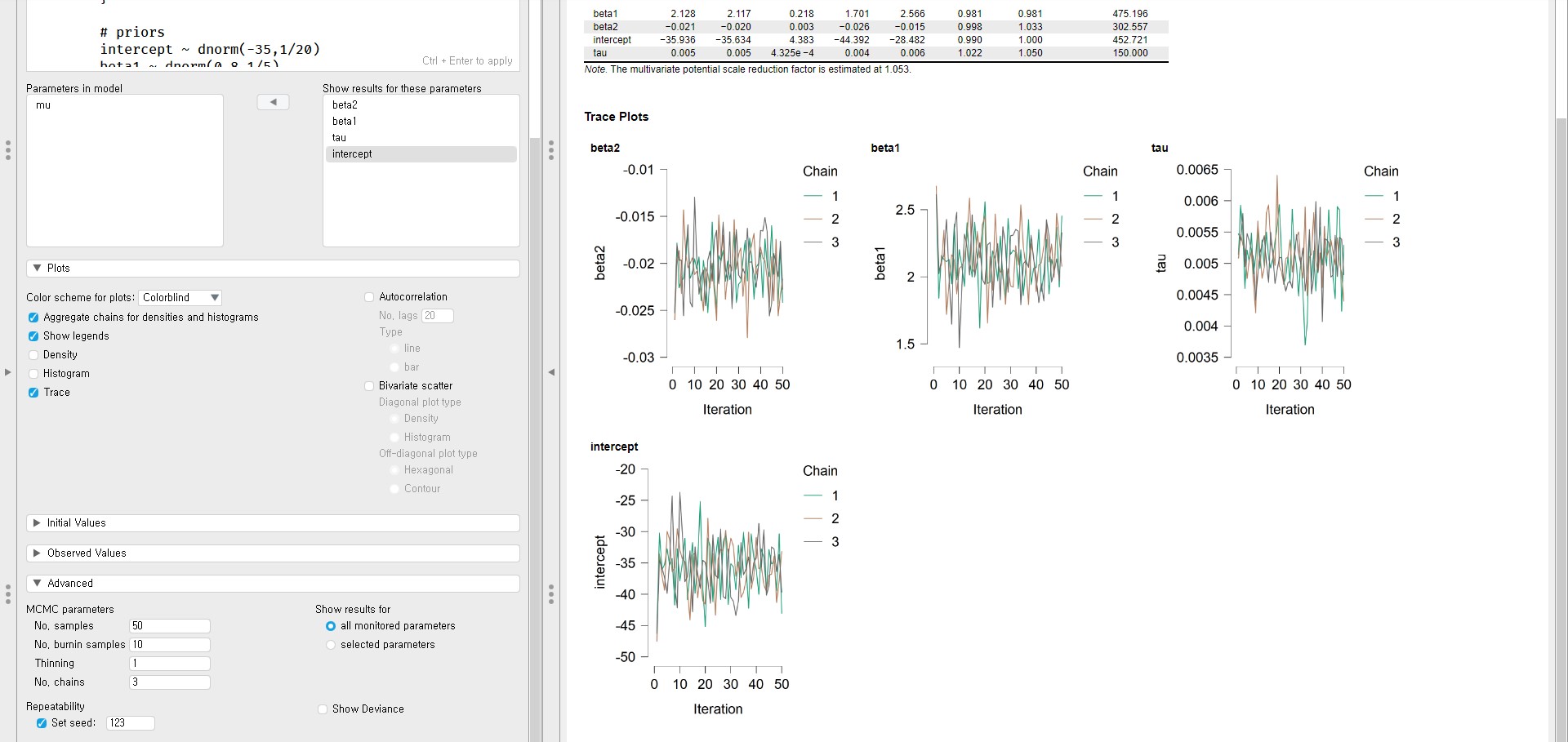

- This time, we use 25000 as the number of burn-in samples and 50000 as the number of samples to take. In total, we use 75000 iterations.

- From the trace plots, we see the fat caterpillar. Let’s also check the Gelman and Rubin diagnostic from the Rhat column of the MCMC Summary table.

- The point estimate and the upper confidence limit are 1.000 for all parameters.

- Therefore, the trace plots and the Gelman and Rubin diagnostics exhibit convergence.

Point 3. Does convergence remain after doubling the number of iterations?

- Following the recommendation in the WAMBS Checklist, we double the number of iterations. This is because the convergence we saw might be a local convergence. Type 50000 as the number of burn-in samples and 100000 as the number of samples. In other words, we use 150000 iterations.

Trace plots and the Gelman and Rubin diagnostics

- Given the trace plots and the Gelman and Rubin diagnostics of all parameters, the convergence remains the same after doubling the number of iterations.

Relative bias

- We can also calculate the relative bias to inspect whether doubling the number of iterations influences the posterior parameter estimates.

- The formula for the relative bias follows: \(bias= 100*\frac{(model \; with \; double \; iteration \; – \; model \; with \; initial \; iteration)}{model \; with \; initial \; iteration\;}\)

- To preserve clarity, we only compute the relative bias of the two regression coefficients, namely beta1 and beta2.

| beta1 | 75000 iterations (converged) | 150000 iterations (double) | Relative bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior mean | 2.141 | 2.141 | 0% |

| beta2 | 75000 iterations (converged) | 150000 iterations (double) | Relative bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posterior mean | -0.021 | -0.021 | 0% |

- In each iteration, the posterior means of the two regression coefficients are the same. Thus, the relative bias should be equal to 0%, and we do not need to worry about the convergence issue.

- Please note that you should take into account the relative bias in combination with the substantive knowledge about the metric of the parameters to determine whether the levels of the relative bias are negligible or problematic. For example, with a regression coefficient of 0.001, a 5% relative bias level might not be substantively relevant. However, in the case of the intercept parameter of 1000, a 10% relative bias level might be quite meaningful. The specific level of relative bias should be, therefore, interpreted in the substantive context of the model.

- As a rule of thumb, if the relative bias is lower than |5|%, you do not need to worry. However, if the relative bias is greater than |5|%, we recommend rerunning the analysis with 4 times the number of iterations.

- We proceed with the following points of the WAMBS Checklist with 75000 iterations.

Point 4. Does the posterior distribution histogram have enough information?

- Before drawing the posterior distribution histogram, uncheck Trace in the Plots tab to save the processing time.

- Check Histogram to draw the posterior distribution histograms for parameters.

- The histograms look smooth and have no gaps or other abnormalities. This indicates the additional iterations are not necessary. Of course, you can increase the number of iterations if you are not satisfied.

- Please note that the posterior distributions do not have to be symmetrical, but they seem to be in the current example.

- Let’s compare these histograms with those based on the first analysis with very few iterations (with 10 burn-in samples and 50 additionally drawn samples).

- Type 50 in No. samples and 10 in No. burnin samples to get the histograms with 60 iterations.

- The difference becomes clear. For example, take a look at the histogram of beta1. The histogram is not smooth and has a gap. The additional iterations are thus necessary in the 60-iteration example.

- Please type 25000 as the number of burn-in samples and 50000 as the number of samples again to proceed with the next point. Uncheck Histogram as well to save the processing time.

Point 5. Do the chains exhibit a strong degree of autocorrelation?

- One evidence of convergence is no autocorrelation within chains. We can inspect if the autocorrelations exist with the autocorrelation plot.

- To draw the autocorrelation plot, check Autocorrelation in the Plots tab.

- The autocorrelation plots show nearly zero autocorrelations within the initial lags.

- If you detect the strong autocorrelation even after a few lags, you have to run the analysis with a lot of samples to identify the whole parameter space (see Link & Eaton, 2012 for more information on autocorrelation check).

Point 6. Do the posterior distributions make substantive sense?

- By plotting the posterior distributions, we can examine whether they are unimodal (i.e., one peak), whether they are centered around one value, whether they give a realistic estimate, and whether they make substantive sense compared to our prior beliefs (i.e., prior distributions).

- In the Plots tab, uncheck Autocorrelation and check Density.

- For the intercept, the highest peak is around -35. This makes substantive sense because the age of 0 for Ph.D. recipients is impossible.

- For both regression coefficients (i.e., beta1 and beta2), the posterior distributions show plausible ranges for the value of regression coefficients.

- For the precision (i.e., tau), the ranges cover positive values. This makes sense because the precision is the inverse of the variance, which cannot be negative.

- Before going to the next stage, uncheck Density to save the processing time.

Stage 3. Understand the exact influence of the priors

- The results with the current priors are presented in the MCMC Summary table in the output panel.

Point 7. Do different specifications of the variance priors influence the results?

- To understand the effects of different prior specifications of precision on the results, let’s use different hyperparameter values for precision.

- The previous setting used \(Gamma(.5, .5)\) as the prior for the precision. This time, we use \(Gamma(.01, .01)\) as a prior.

model{

# likelihood

for (i in 1:333){

mu[i] <- intercept + beta1 * E22_Age[i] + beta2 * E22_Age_Squared[i]

B3_difference_extra[i] ~ dnorm(mu[i],tau)

}

# priors

intercept ~ dnorm(-35,1/20)

beta1 ~ dnorm(0.8,1/5)

beta2 ~ dnorm(0,1/10)

tau ~ dgamma(0.01,0.01)

}- Don’t forget to press Ctrl and Enter together to apply the changes!

- The following table presents the comparison of posterior means between different prior specifications alongside the relative bias.

| Parameters | \(Gamma(.01, .01)\) | \(Gamma(.5, .5)\) | Relative bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -36.176 | -36.180 | \(100*\frac{(-36.176\; – \; (-36.180))}{-36.180}\) = -0.01% |

| beta1 | 2.141 | 2.141 | 0% |

| beta2 | -0.021 | -0.021 | 0% |

| tau | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0% |

- The relative bias for the intercept is almost 0 whereas those for other parameters are 0. Therefore, the results are robust.

Point 8. Is there a notable effect of the prior when compared with non-informative priors?

- To compare the effect of the non-informative priors with that of the informative priors, we need to run the analysis with the non-informative priors. We then compare the output with what we have done so far with the informative priors.

- For the non-informative priors, we borrow the default priors that the R package blavaan (Merkle & Rosseel, 2018) uses with the JAGS target.

- For more information, we refer readers to JASP for Bayesian analyses with informative priors (using JAGS) and Bayesian Regression in Blavaan (using JAGS).

- Following the default prior settings that blavaan employs, we are going to specify the noninformative priors as:

- \(intercept \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1e-3)\)

- \(\beta_1 \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1e-2)\)

- \(\beta_2 \sim \mathcal{N}(0, 1e-2)\)

- \(tau \sim Gamma(1, 0.5)\)

- For your convenience, we provide the code that you can copy and paste!

model{

# likelihood

for (i in 1:333){

mu[i] <- intercept + beta1 * E22_Age[i] + beta2 * E22_Age_Squared[i]

B3_difference_extra[i] ~ dnorm(mu[i],tau)

}

# priors

intercept ~ dnorm(0,1e-3)

beta1 ~ dnorm(0,1e-2)

beta2 ~ dnorm(0,1e-2)

tau ~ dgamma(1,0.5)

}- Press Ctrl and Enter together to apply the changes.

- The subsequent table summarizes the comparison of posterior means between non-informative and informative priors alongside the relative bias.

| Parameters | Non-informative priors | Informative priors | Relative bias |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | -40.711 | -36.180 | \(100*\frac{(-40.711\; – \; (-36.180))}{-36.180}\) = 12.52% |

| beta1 | 2.356 | 2.141 | \(100*\frac{(2.356\; – \; 2.141)}{2.141}\) = 10.04% |

| beta2 | -0.023 | -0.021 | \(100*\frac{(-0.023\; – \; (-0.021))}{-0.021}\) = 9.52% |

| tau | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0% |

- Except for the precision, the informative priors have influences on the posterior means ranging from 9.52% to 12.52% compared to the non-informative priors.

- Importantly, you have to keep in mind where the priors come from. If your informative priors come from accurate and reliable sources, you should use them. Simultaneously, we recommend you to have good arguments behind the usage of the informative priors. If you do not have trustful sources for the prior distributions, however, you should use the non-informative priors.

Point 9. Are the results stable from a sensitivity analysis?

- The idea of the sensitivity analysis is that it tells us how robust the estimates are depending on the specifications of the prior distribution.

- To investigate the stability of your results with the sensitivity analysis, you can adjust the hyperparameters of the priors upward and downward, thus re-estimating the model with varied priors to check for robustness (see Van Erp, Mulder, & Oberski, 2018 for more information on the sensitivity analysis).

“If informative or weakly-informative priors are used, then we suggest running a sensitivity analysis of these priors. When subjective priors are in place, then there might be a discrepancy between results using different subjective prior settings. A sensitivity analysis for priors would entail adjusting the entire prior distribution (i.e., using a completely different prior distribution than before) or adjusting hyperparameters upward and downward and re-estimating the model with these varied priors. Several different hyperparameter specifications can be made in a sensitivity analysis, and results obtained will point toward the impact of small fluctuations in hyperparameter values. […] The purpose of this sensitivity analysis is to assess how much of an impact the location of the mean hyperparameter for the prior has on the posterior. […] Upon receiving results from the sensitivity analysis, assess the impact that fluctuations in the hyperparameter values have on the substantive conclusions. Results may be stable across the sensitivity analysis, or they may be highly instable based on substantive conclusions. Whatever the finding, this information is important to report in the results and discussion sections of a paper. We should also reiterate here that original priors should not be modified, despite the results obtained.”

Point 10. Is the Bayesian way of interpreting and reporting model results used?

- Finally, it is time to interpret and report models that we constructed with the informative priors. You can find the JAGS model specification below (it is the same code that we used at the beginning of Stage 2). Copy and paste the code into the Enter JAGS model below section. Don’t forget to press Ctrl and Enter!

model{

# likelihood

for (i in 1:333){

mu[i] <- intercept + beta1 * E22_Age[i] + beta2 * E22_Age_Squared[i]

B3_difference_extra[i] ~ dnorm(mu[i],tau)

}

# priors

intercept ~ dnorm(-35,1/20)

beta1 ~ dnorm(0.8,1/5)

beta2 ~ dnorm(0,1/10)

tau ~ dgamma(0.5,0.5)

}- In the output panel, the results are presented in the MCMC Summary table.

- Although we present how to interpret the parameter estimates, please refer to Van de Schoot and Depaoli (2014) for a summary of how to interpret and report models thoroughly.

- The posterior mean of the regression coefficient of age (beta1) is 2.141. We interpret this value such that a one-year increase in age adds about 2.141 delays in the Ph.D. projects on average. The 95% credible interval of age is [1.731, 2.550], which means that there is a 95% probability that the regression coefficient of age lies in the population with the corresponding credible interval. Since the 95% credible interval does not include 0, there is the evidence of the effect of age in predicting the Ph.D. delay.

- The posterior mean of the regression coefficient of age-squared (beta2) is -0.021. This can be interpreted such that one unit increase of the age-squared variable leads to a decrease of 0.021 unit in the Ph.D. delay on average. The 95% credible interval of age-squared is [-0.026, -0.015]. This indicates that we are 95% sure that the regression coefficient of the age-squared variable lies within the corresponding interval in the population. Therefore, it is fairly sure that there is an effect of the age-squared variable in predicting the delay.

Epilogue

- Congratulations! You have successfully finished the current tutorial. We hope you found it informative and useful.

- As explained in Depaoli and Van de Schoot (2014), the WAMBS Checklist is a guideline to implement the Bayesian statistics and write up the findings, hence contributing to the research transparency and replicable results. We wish this tutorial can assist and benefit a lot of substantive researchers who use JASP for performing Bayesian analyses!

References

Depaoli, S., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Improving transparency and replication in Bayesian statistics: The WAMBS-Checklist. Psychological methods, 22(2), 240-261. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000065

JASP Team (2020). JASP (Version 0.13.1)[Computer software].

Merkle, E., & Rosseel, Y. (2018). blavaan: Bayesian Structural Equation Models via Parameter Expansion. Journal of Statistical Software, 85(4), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v085.i04

Lynch, S. M. (2007). Introduction to applied Bayesian statistics and estimation for social scientists. Springer Science & Business Media.

Link, W. A., & Eaton, M. J. (2012). On thinning of chains in MCMC. Methods in ecology and evolution, 3(1), 112-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00131.x

Van de Schoot, R. (2020). PhD-delay Dataset for Online Stats Training [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3999424

Van de Schoot, R., & Depaoli, S. (2014). Bayesian analyses: Where to start and what to report. The European Health Psychologist, 16(2), 75-84.

Van de Schoot, R., Yerkes, M. A., Mouw, J. M., & Sonneveld, H. (2013). What took them so long? Explaining PhD delays among doctoral candidates. PloS one, 8(7), e68839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068839

Van Erp, S., Mulder, J., & Oberski, D. L. (2018). Prior sensitivity analysis in default Bayesian structural equation modeling. Psychological Methods, 23(2), 363-388. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000162